‘It’s OK to cry’: Viral nurse photo highlights a sometimes forgotten toll

Debra Melani | College of Nursing Nov 21, 2019

For Kim Paxton, it was the young father shot in the back of the head after opening the store safe for two masked men. The robbers left with $100.

For Mary Beth Flynn Makic, it was the man who drove into the path of a semi-truck, his body broken beyond repair.

And for Caty Nixon, whose viral photo recently grabbed national attention and put the spotlight on the nursing profession, it was the stillborn baby she helped deliver.

For all three nurses, it was a time they cried.

And that’s OK, said University of Colorado College of Nursing critical-care expert Flynn Makic.

Distraught nurse post grabs national attention

“I was so pleased that they showed the human side of nursing,” Professor Flynn Makic, PhD, said of the TV news segment that caught her attention one night while making dinner. She saw the photo of the Texas nurse, sitting in a living-room chair still in blue scrubs and covering her face as she sobbed.

Nixon, a labor and delivery nurse, had stopped by her twin sister’s house after a 53-hour, four-day stretch of shifts that ended in a stillbirth. Her sister snapped a picture of her during her breakdown and posted it, writing a tribute to her sibling and to the nursing profession. It went viral, gaining widespread media attention.

When many of CU Nursing’s professors were in college, their instructors taught them that it is not OK to cry, Flynn Makic said. Today, with nursing shortages telling a tale, and scores of studies focused on burnout in the profession, that advice has changed, she said.

CU Nursing professors say ‘It’s OK to cry’

“We experience those emotions with patients, sometimes profoundly, especially in labor and delivery,” said Assistant Professor Lisa Diamond, DNP, referring to Nixon’s breakdown. “Most of the time, it’s a happy place, but when it’s not, it’s really bad.”

Nurses do bond with patients and their families, particularly in critical care, where patients often remain hospitalized for months, Flynn Makic said.

“When they die, you do experience a loss,” said Flynn Makic, who formed a relationship with the wife and teenage daughters of the man struck by the semi-truck, attending his funeral when he died. She later made a video highlighting the experience, titling it “It’s OK to Cry.”

“I think when we fail to acknowledge that loss, when we fail to be human and do this craft pretending it didn’t hurt, that’s when we start to have burnout,” she said.

‘Things don’t stop because a person died’

More than 25 years later, Assistant Professor Kim Paxton, DNP, still cannot recount the gunshot victim scene without tears.

Lead trauma nurse at the time, Paxton said the young man went into cardiac arrest within 15 minutes of arriving in the ER. “We worked on him for an hour, but we lost him,” said Paxton, recalling the wife’s wails as she and the doctor told her, her two toddlers at her feet, that her husband was gone.

Paxton said she and her fellow caregivers hugged and cried in private for a few minutes, and went right back to work. “In the emergency room, things don’t stop because a person died,” Paxton said.

And that’s part of the problem, Flynn Makic said.

Factors behind caregiver burnout abound

“The current environment is like: Oh, OK, get the room cleaned up, and let’s get another patient in here,” Flynn Makic said. “I think we need to honor what happened, and we need to pause. Give us a few minutes to decompress,” she said. “I think if we did that categorically in practice, resilience would just really increase.”

Many other aspects in the financially driven, understaffed medical environment must change for the sake of the caregivers, Flynn Makic said. We’re losing docs. We’re losing nurses. Suicide rates for providers are through the roof,” she said, pointing out how Nixon had just worked 53 hours in four days.

“When you’re fatigued, it’s really hard to stay resilient,” she said. “Not only that, if you are fatigued, you are at more risk of making an error, which would lead to more emotional trauma for the nurse.”

Journaling: ‘There’s power in it’

To persevere at the bedside, nurses must take care of themselves, said Flynn Makic, a trauma nurse for years who responded during the Columbine and Aurora theater shootings. “I tell my students to be a caring nurse requires emotion, and so you have to identify and cope with the emotion to stay resilient.”

Diamond, who notes that the stress of the high-demand nursing profession begins in college, recently began having students in one of her classes journal each month with a focus on the emotional side. Diamond hopes that the student will continue the practice in their professional lives.

However they choose to do it, all nurses need to follow Nixon’s cue and let their emotions out, Flynn Makic said.

“There is power in it. The science has shown us that if we can un-bottle our emotions, we can process them,” she said, adding that even unloading on a twin sister has its benefits. “Find a way that you can process the information so that you can stay resilient and continue to care with your whole heart.”

***

Why releasing emotions for nurses matters

During a study published in the American Journal of Critical Care looking at the feasibility of resilience training for Intensive Care Unit nurses, CU Nursing alumna Meredith Mealer, PhD, and colleagues found that of the ICU nurses surveyed:

- 100% were positive for symptoms of anxiety.

- 81% were positive for emotional exhaustion.

- 77% were positive for symptoms of depression.

- 44% met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

***

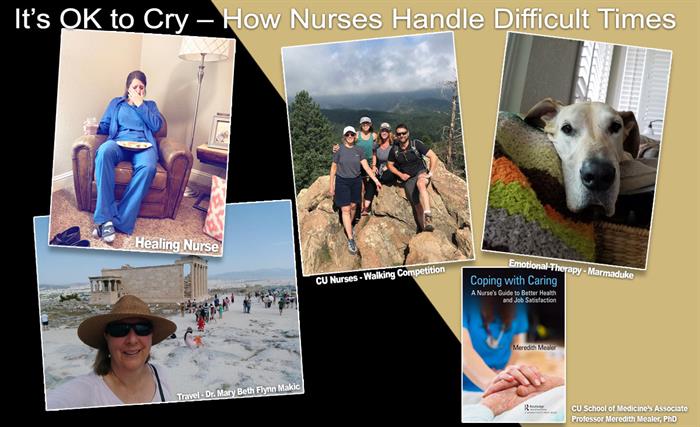

Tips for managing difficult emotions

In her new book released in July, the School of Medicine’s Associate Professor Meredith Mealer, PhD, offers a number of tips on releasing emotions. “Coping with Caring: A Nurse’s Guide to Better Health and Job Satisfaction” highlights strategies, including cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness practices.

- Other tips for releasing emotions from CU Nursing professors:

- Getting adequate sleep.

- Ensuring good nutrition.

- Getting regular exercise.

- Meeting with colleagues who experienced the same trauma afterward for an informal “debriefing,” whether it’s over breakfast or beers.

- Talking to loved ones (keeping in mind that sometimes only colleagues can completely empathize).

- Using your own pets for therapy.

- Travel, take “me time.”

- Hobbies, from knitting to music.